For thousands of years, learning the world, people were constantly trying to explore the mysteries of the human body structure. The ancient astrologers imagined the Universe as a big human body divided into 12 parts, where each one was controlled by a corresponding constellation.

The philosophers of Ancient Greece envisioned a human as a "microcosm" – just as a "macrocosm" (a symbol of the Universe). These ideas were developed by the medieval scholastics and thinkers of the Renaissance, for whom a human was the center of the Universe, and proportionality to the human body was the measure of beauty.

Renaissance medical scientists, with the permission of the Church, began performing public dissections of corpses, turning this process into a spectacle called "Anatomical theatre".

One of the first such theatres was built in Padua in 1594 and included six round-shaped galleries located above the central table where a prosector was working. The building accommodated from 200 to 300 viewers, who were seated according to their status and significance in urban life. The first row was intended for professors of anatomy, faculty of the medicine department of the University, and city officials. The second and the third rows were occupied by medical students and the rest – by the city public. The audience paid for the entrance, and refreshments and music were at their service.

The exposition of this hall is presented in two sections. The first is the "Anatomical theatre" itself, which displays exhibits from the collection of the famous Russian surgeon I.V. Buyalsky, including his work – the death mask of A.V. Suvorov, as well as anatomical preparations and models, autopsy tools, and the anatomical graphic works of the 16th – early 18th centuries from the Museum's collection.

The second section is like a classroom, which contains interactive tablets illustrating the structure and functioning of various organs and systems of the human body, original autopsy reports from anatomical theatres of the 19th century.

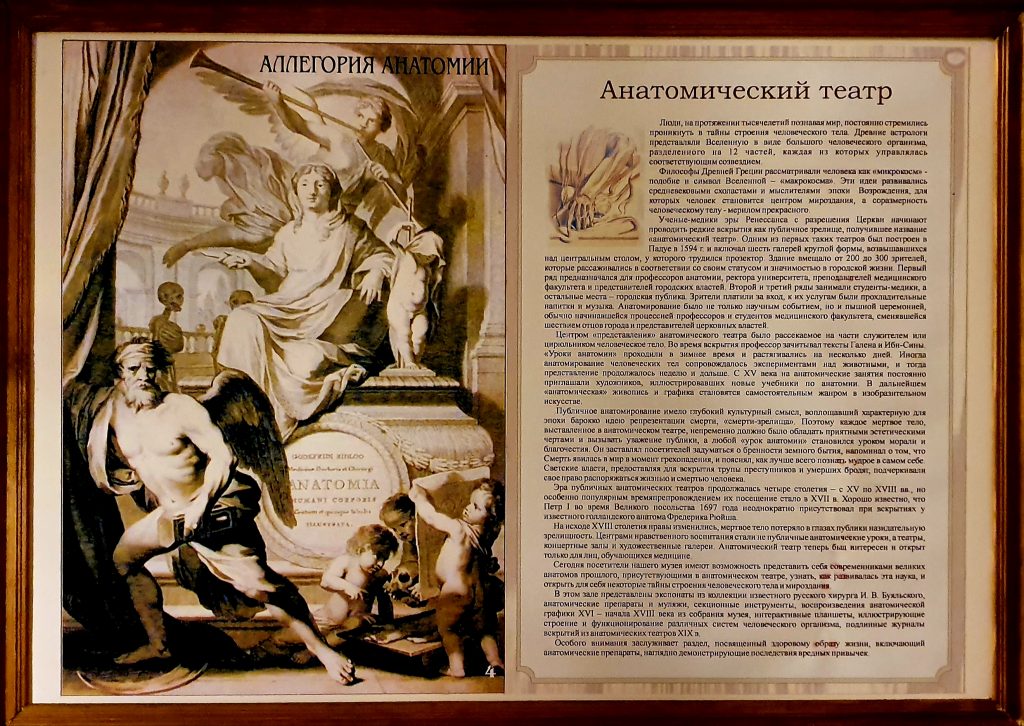

The central place of the hall is occupied by a banner, which depicts an engraving replica - frontispiece (illustration in the book, located on the left side of the title pages) of the scientific anatomy founder Andreas Vesalius’s work "On the fabric of the human body…" (“De corporis humani fabrica libri septem”). This work, consisting of seven books, is briefly called “Fabric” (from Latin fabrica - structure). The author of the frontispiece of “Fabric” is the artist Joannes Stephanus Calcarensis (Titian’s student), who depicted, in allegorical form, one of the anatomical theatres of those times. The central figure is Vesalius himself; here you can also see the portraits of Andreas Vesalius’s contemporaries - his supporters and enemies.

From the 15th century, artists who illustrated new textbooks on anatomy were constantly invited to anatomical classes. Public dissection had a deep cultural meaning, embodying the typically Baroque idea of representing death – "death-spectacle". The "lesson of anatomy" became a lesson of morality and piety.

The era of public anatomical theatres lasted for four centuries - from the 15th to the 18th centuries, but visiting them became especially popular in 17th century. It is well known that Peter I, during the Grand Embassy of 1697, was repeatedly present at autopsies performed by the famous Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch.

By the end of the 18th century morals had changed, and a dead body lost its didactic attraction for public. The anatomical theatre was now interesting only for medicine students.